D&D5e does not include an entry for titans. Rather, the term is used to describe certain creatures of immense power and legendary status. The kraken and the tarrasque are “titans,” in this sense. Yet the classic creature, going back to the early days of 1st and 2nd Editions, remains in the latest version as the Empyrean, a celestial being with the titan descriptor. There are certain qualities in this version that match with earlier editions (excluding 4th, where titans are envisioned as prior or later evolutions of giants, more on that in a moment), such as their massive hammers (the Maul of the Titans), a suite of spell-like abilities, their immortality and their connection with nature (manifesting as subtle changes to their environment based on the titan’s “mood”).

Of course, I don’t run 5e and I generally consider it to be a shameless corporate attempt to capitalize on perceived market factors such as nostalgia and the community’s desire for story-driven games. I started D&D with the 2nd Edition in the ’90s, and I played a bit of 4th Edition when it first released, but the bulk of my experience is with 3rd. Thus, for my current game, while I focus heavily on 2e there are times when I want something more, so I cast about to different editions for inspiration. This has proven rather useful for where classes, special abilities, spells and the like are concerned; but for a fantasy bestiary . . .

Take, for instance, the entry on titans from the 3rd Edition Monster Manual:

Titans are wild and chaotic, masters of their own fates. They are closer to the wellsprings of life than mere mortals and so revel in existence. They are prone to more pronounced emotions than humans and can experience deitylike fits of rage. Many titans are powerful servants of good, but in ages past the race of titans rebelled against the deities themselves, an a number of titans turned to evil. An evil titan is an indomitable tyrant who often masters entire kingdoms of mortals. - MM3e, p.243

This is all the more we get for the creature, a mere five sentences while the rest of the information covers a full page of text. And this is a problem with the overall book, as 3e’s approach is to give more game statistics and mechanics, than to provide anything that would be considered “fluff.” Yet this fluff is instrumental to running a fully-realized world, where the players connect with the DM’s content on a personal level, deeper than simply tossing dice and moving plastic figures across the board.

3e is even more useless when we consider that the description is lifted near verbatim from the 2e text:

Titans are livers of life, creators of fate. These benevolent giants are closer to the well springs of life than mere mortals and, as such, revel in their gigantic existences. Titans are wild and chaotic. They are prone to more pronounced emotions that [sic] humans and can experience godlike fits of rage. They are, however, basically good and benevolent, so they tend not to take life. They are very powerful creatures and will fight with ferocity when necessary. To some, titans seem like gods. With their powers they can cause things to happen that, surely, only a god could. They are fiery and passionate, displaying emotions with greater purity and less reservation than mortal beings. Titans are quick to anger, but quicker still to forgive. In fits of rage they destroy mountains and in moments of passion will create empires. They are in all ways godlike and in all ways larger than life. And yet is [sic] should be noted that titans are not gods. They are beings that make their home in Olympus and walk among the gods. Yet they are not omnipotent, omniscient rulers of the planes. Sometimes their godlike passions and godlike rages make them seem like deities, however, and it is common for whole civilizations to mistake them for deities. - AD&D, 2nd Edition, Monster Manual, pp.343-344

This is one of the reasons I’ve been going back to 2e, that their books seemingly offer more in the way of content which I can use to build my world; but even so, if we look more closely at this passage, we find some rather confusing elements.

We’re told that titans are “wild and chaotic,” though this does not jive with actual mythology and ancient stories. (Put a pin in that, we’ll come back to it.) They are, basically, “good and benevolent” yet they have the tendency to “destroy mountains” in a “fit of rage.” “Some” people see titans as gods but we’re told they’re not gods . . . despite having a list of 27 spell-like powers, usable at-will, in addition to the full spellcasting potential of a 20th-level cleric or mage. We’re told that they’re like mortal men, only larger and more connected to the “well springs of life” ~ a concept that isn’t explained further ~ but it’s difficult to see how they’re more like mortals than the immortal deities of the world, given the whole picture emerging from the sum of their parts.

For the purpose of my world ~ where I’ve defined giants as guardians of the Dreaming and a meta-physical manifestation of the Seven Deadly Sins / Heavenly Virtues ~ I need a way to contextualize titans. I use real-world pantheons, mythology and ancient beliefs as the basis for gods and religions, and as such, titans have a place within the Greek-inspired pantheon. Thus, if I want to keep them, I need to explore that history.

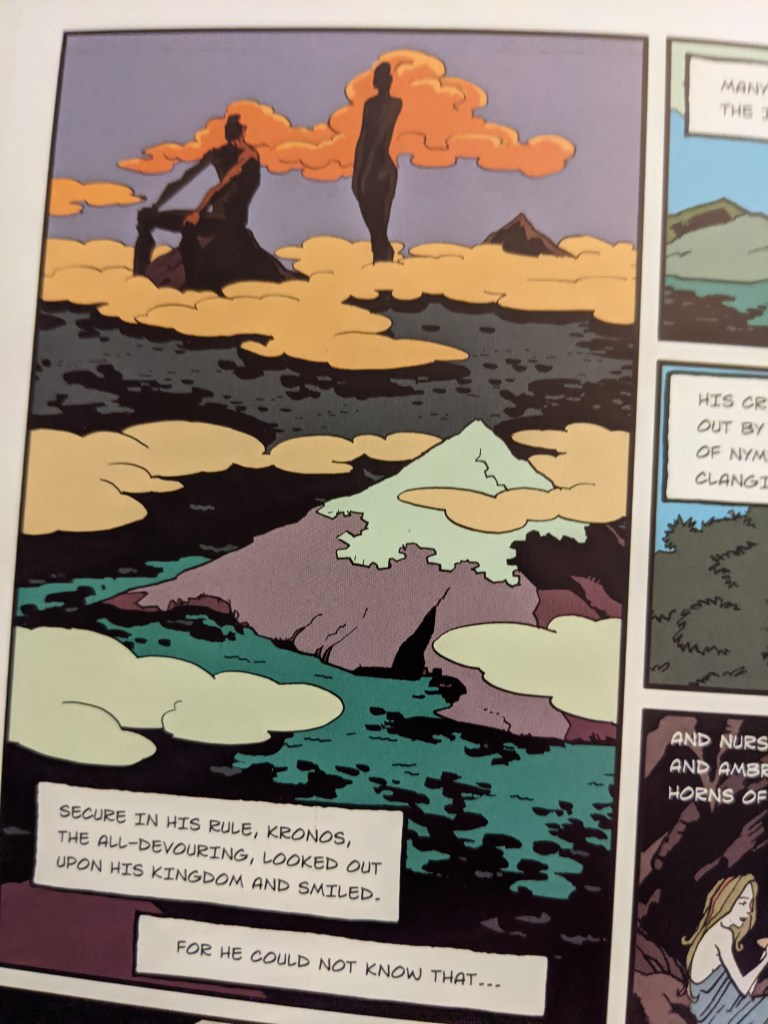

The Titans were the former gods, the generation of gods preceding the Olympians. They were overthrown as part of the Greek succession myth, which told how Cronus seized power from his father Uranus, and ruled the cosmos with the Titans as his subordinates, and how Cronus and the Titans were in turn defeated and replaced as the ruling pantheon of gods, by Zeus and the Olympians, in a ten-year war called the Titanomachy. As a result of this war of the gods, Cronus and the vanquished Titans were banished from the upper world, being held imprisoned, under guard in Tartarus, although apparently, some of the Titans were allowed to remain free. - Wikipedia

Titans were the gods that came before the gods. Indeed, their ascension to a godlike status involved deposing the ruler of the cosmos that came before them. This progression parallels the natural progression in the mortal world, where the parents are succeeded by their children, and their children after them. Of course, the specific details of this origin myth provide clarification, such as the idea that this transition of rulers isn’t exactly good.

Indeed, the specifics of this myth clearly demonstrate a critical element about rulership: that the victor dictates the structure of their world and writes its history, in an effort to justify and further their claim to power. Ouranus (or Uranus) was the sky god, as Gaia was the earth goddess, and together they were the parents of the titans. As the titans rebelled against their parents and slew Ouranus, draining his blood into themselves and achieving a measure of his power, they took his place as rulers of the world. As rulers of the world, they were in charge of writing the history of their rebellion. The story we get is that Ouranus was appalled and disgusted by his other children (the cyclopes and hekatonkheires), and had them imprisoned deep within the earth. This caused Gaia pain and she urged the titans to fight back, providing them the means to dispatch Ouranus.

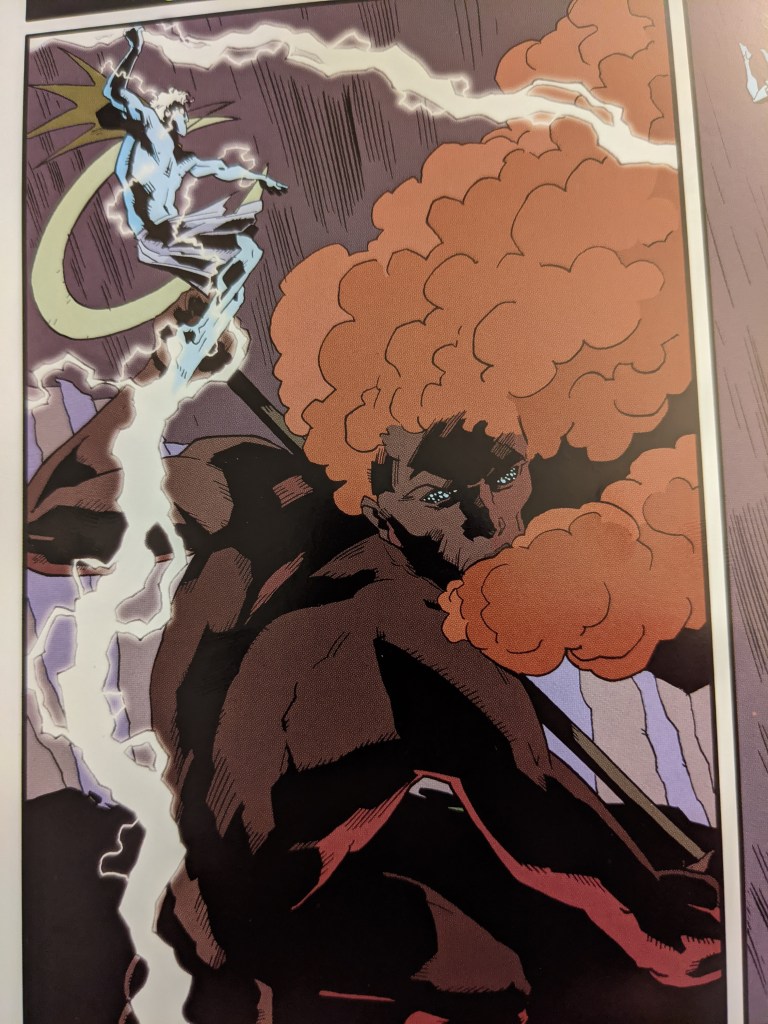

Of course, the story we actually get comes from a time when the Greek pantheon ~ Zeus, Hera, Apollo and the rest ~ were in power, thus it’s fair for us to question how much of this myth was rewritten to favor their ascension. (Probably all of it, honestly.) The Olympians were children of Cronus, the titan who slew Ouranus and who took his place as ruler of the world. Cronus did not everything that his mother instructed (such as freeing the cyclopes and hekatonkheires) and Gaia predicted that his children would one day depose him. In true prophetic fashion, Cronus tried to prevent this by swallowing his children whole, but the plan was thwarted by his wife, Zeus was raised in the mortal world, and eventually the New Gods (the Olympians) were freed from imprisonment, and fought and defeated the titans.

As the Olympians are the powers in charge of the current Greek-inspired pantheon, their tale should be viewed from this perspective: that they rebelled against the existing power structure, took its place and favored a narrative that justified their rule.

This progression can be seen, at least in part, in 4th Edition’s characterization of titans:

GIANTS ARE HULKING HUMANOID CREATURES with fundamental ties to the world, be that bedrock, uncontrollable fires, raging storms, or inevitable death. The first giants were massive titans of fire and frost, storm and stone. These giants labored under primordial lords to shape the newly forming world. - D&D, 4th Edition, Monster Manual, p.120

Here, titans have a direct connection with giants instead of gods, and giants have a direct connection with the Elemental Chaos. A titan, therefore, is something of a primordial version of a giant: before there were giants, there were titans; and giants are the lesser form of these ancient beings. Whether this means that giants in the current age “grow” or “evolve” into titans, or if titans become giants because of limitations placed upon them, is not entirely clear. Regardless, the mechanics for titans and giants make this relationship clear and it’s one that I genuinely like. I have a preference for neat, orderly systems, and the idea that titans bear this relationship with giants is one that fits within such a system.

I probably won’t go that direction because I’ve already defined a place for giants in my world, but the connection ~ that of a parental/offspring relationship, of a progenitor and successor ~ seems a critical aspect of the inherent nature of titans.

. . . and as I think of it, it makes sense that 4e would link the Elemental Chaos to titans, given what we’ve seen in earlier editions about them being “wild and chaotic.” This doesn’t work, of course, because of the mythological tales: titans rebelled against the existing order and hierarchy, but rebellion itself is not inherently chaotic. They replaced Ouranus as rulers of the world but they did not change the fundamental nature of that rulership. They were deposed by their children, the Olympian gods, but again, the systemic nature and hierarchy did not change . . . so far as we know, given that the tale is only available to us through the current ruling class.*

(*let’s also note that, when I speak of the Olympian gods as a ruling class or social hierarchy, I’m really talking about the priests and poets responsible for repeating their stories throughout the ages.)

In this manner, I believe we can view titans as representing a specific aspect of human nature: tyranny.

The Titans, according to Paul Diel, symbolize "the brute strength of Earth and hence earthly longings in rebellion against the spirit (Zeus)" (DIES p.102). Together with the Cyclopes, Giants and Ouranids . . . they stand for the upheavals of nature at the beginning of time, "elemental manifestations, . . . the savage untamed strength of Nature in her birth-pangs. They represent the first stage of evolutionary gestation, the eruptions which prepared the Earth to become the place where human life could burgeon" (DIES p.112) . . . Furthermore, in their struggle against the spirit, the Titans not only symbolize the forces of nature but also the "tendency towards dominance ~ tyranny. This tendency is all the more to be feared since it is sometimes hidden under an obsessive ambition to make the world a better place" (DIES p.144). - Dictionary of Symbols, pp.1009-1010

Of course, bringing this perspective into play helps to justify the 4e connection with the Elemental Chaos and helps make sense of the “wild and chaotic” description from 2e; but the more important detail is that titans are symbolic of tyranny.

Throughout history, the ruling class has always viewed themselves as deserving of rule. They were not only selected or given this power, but they’re better than the people they rule over. They’re position isn’t a service, it’s a right. It’s Manifest Destiny.

It’s also, interestingly, a characteristic of human nature: this tendency to view ourselves as better than our peers, deserving power over others, leading to deliberate attempts to consolidate that power and exercise control.

There’s this article from the anthropologist Richard Borshay Lee, working in the Kalahari in the 1950s and ’60s, where Lee learns a lesson about the !Kung people. Lee had been living with the !Kung and studying their society for some time, when he decided he wanted to pay them back for their help in his research. He bought an ox, the largest he could find, and planned to share it with the tribe during an annual feast. The animal was large enough to provide three or four pounds of meat, in addition to fat and bones, per person in the tribe. Yet when Lee told the !Kung tribesmen of his plan, he was met with ridicule and derision. He was told the animal was “too thin,” little more than “skin and bones,” despite the fact that it was obviously fat and healthy. And this was more than gentle ribbing, too. Lee met not a single tribesman who would acknowledge the gift he was providing; instead, the kindest response was a begrudging acknowledgement that the beast would be eaten regardless, because “it’s food” and the Bushmen could not afford to pass up the offer.

Lee was frustrated by these circumstances, partly because the !Kung response was so consistent and convincing, and partly because it was obviously inaccurate. There must have been some angle he was missing. And there was: turns out the behavior was something of a tradition, where the tribe would always respond to a hunter’s kill with words of derision and scorn. Perplexed further, Lee sought the insight of a friend within the tribe:

“But,” I asked, “why insult a man after he has gone to all that trouble to track and kill an animal and when he is going to share the meat with you so that your children will have something to eat?” “Arrogance,” was his cryptic answer. “Arrogance?” “Yes, when a young man kills much meat he comes to think of himself as a chief or a big man, and he thinks of the rest of us as his servants or inferiors. We can’t accept this. We refuse one who boasts, for someday his pride will make him kill somebody. So we always speak of his meat as worthless. This way we cool his heart and make him gentle.” - Eating Christmas in the Kalahari, 1969

This revelation is in keeping with other anthropological studies. For instance, there are several theories for mankind’s development of humor, ranging from the enabling of good social relationships to being a tool that downplays unimportant topics. There’s a theory that holds social egalitarianism as a key factor to hunter-gatherer societies because the risk of authoritarianism ~ of tyranny ~ threatens the tribe’s continued existence. We may also draw a connection to concepts of polyandry (necessary in societies where men engage in violent or dangerous tasks, and thus their mortality rate is higher than the women, and monogamy inhibits the formation of social bonds between adults and children) or property ownership (not as prevalent since possession of things can compel people to hold their personal interests above that of the tribe, especially where inheritance is concerned) within pre-historical societies . . . connections that change significantly once agriculture, permanent settlements and the priestly (ruling) class come into play.

In this manner, we might argue that titans represent the transition from the pre-historical to the ancient world, which I find in keeping with other elements like their connection to the natural world (5th Edition’s “manifest emotion” ability), their immortality (the persistence of the natural world), and their immense strength and power (a full suite of abilities that place them on par with the gods).

. . . although that makes me ask the question: what, exactly, is it that separates the gods from beings like titans? (Because, let’s face it, there are other entities in the ‘verse that are just as powerful and ancient.)

I mean, apart from the obvious . . .

Leave a Reply